Besides the obvious situation the league finds itself in, this NBA season has been without recent precedent in one other way. For the first time in more than a decade, the 2019-2020 NBA league year does not include a “Super-Team” among its two conferences. Sure, there are super-star players coordinated together in different cities in an effort to bring themselves a title. You don’t need to look any further than either Los Angeles team in order to see that. But largely, of the major contenders that will exist when the NBA makes its hopeful return at the end of July, it will be a group- the Bucks, Raptors, Nuggets and Jazz, for instance- devoid of the kind of “Big Three” (or more) that has run roughshod over the league since the Lakers and Celtics came to blows in the 2008 Finals.

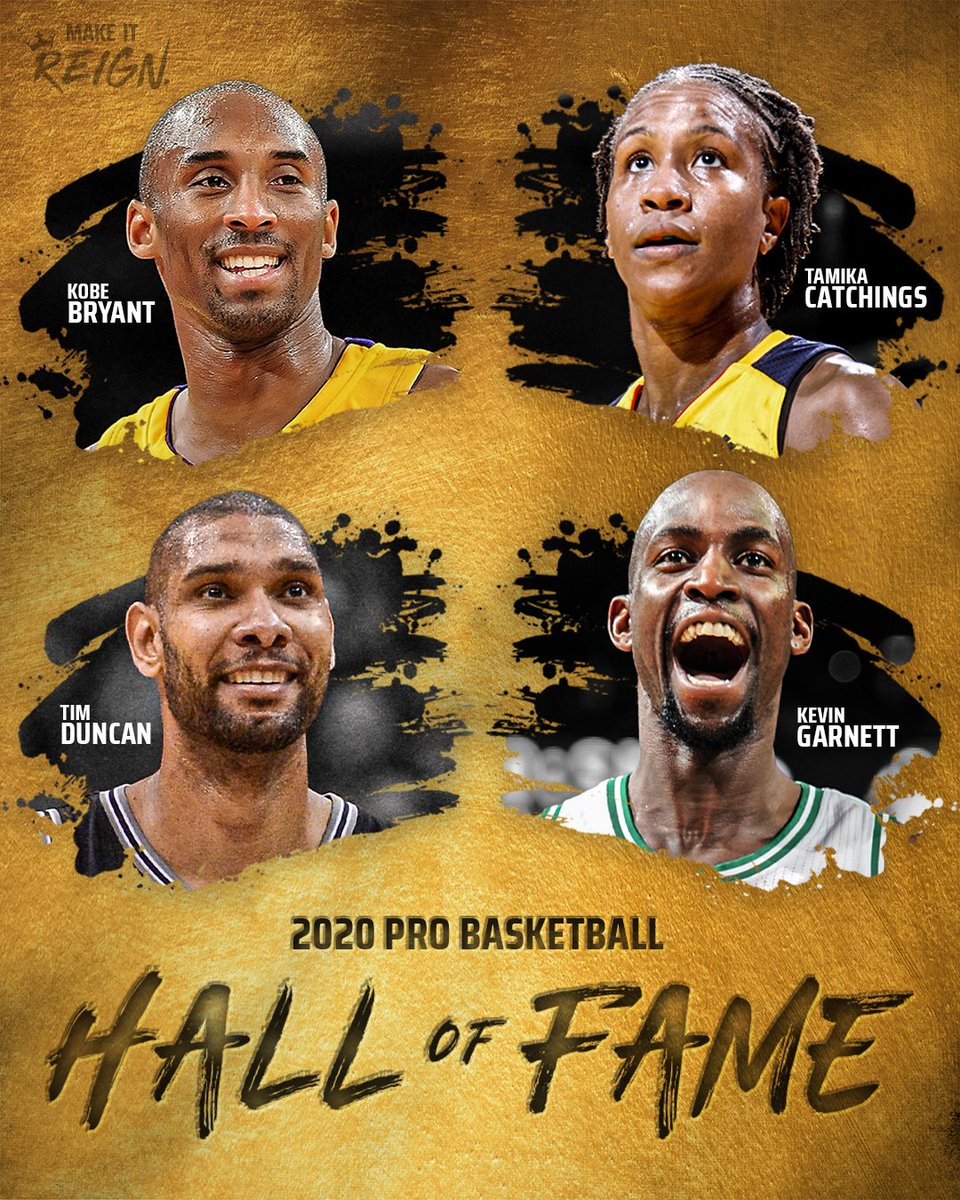

In a year where a vile disease has forced nostalgia upon us sports fans, it is ironic that the 2020 NBA landscape looks a lot more like the landscape of the ‘90s than 2019. The answer for how we got here in 2020 is one of simple circumstance. Super-teams have burned themselves out. They aren’t sustainable. Prime players age out of their prime (see photo). Egos eventually collide and big pieces want to go their separate ways. One or two poorly placed injuries take a Super-Team out of contention. LeBron-led teams burn through their assets trying to keep their best player and best chance to win a title in the best position to do so. Most of this is a matter of circumstance and league rules, and while a lottery trip for the Golden State Warriors combined with a healing roster could disprove my theory, for the moment it stands unrefuted.

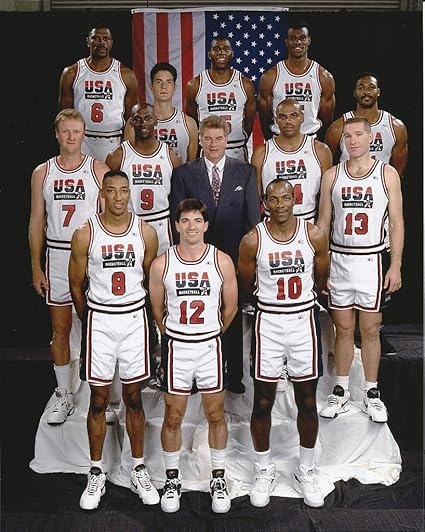

But what about the past? Why were Super-Teams, at least in the way we think of them today, conglomerations of established star players, not a thing before 2008?

Well for one, the health and structure of the game made the 2010s possible. While the NBA has been a salary cap league both now and in the 90s, in the past Collective Bargaining Agreement between the league and its players it was established that no player can be paid more than 35% of a team’s cap room. He also cannot be signed for more than 5 years. This is known as the Super-Max contract. No such thing existed in 1997, because contracts had no such restrictions. Knicks’ star center Patrick Ewing soaked up 76 percent of the Knicks salary cap in the 1997-1998 season. Spurs center David Robinson took up 46 percent of it in the same year. When players from the 90s say that in their day they wanted to win on their own as a matter of pride and when they claim it’s in bad taste to team up with other stars, just know that is its easy for them to sing that tune. The climate of the time never really presented them the opportunity for anything else. The rules of the time lent themselves to that type of one, or at most two, stars per team- prove to be the bigger alpha- mentality.

What if that wasn’t the case? In 1988 Tom Chambers officially became the NBA’s first unrestricted free agent, and while the first several off-seasons of NBA free agency were fairly hum-drum, the first small step towards the culture we are more familiar with today would occur in the summer of 1996.

It wasn’t a large step, but it was an important one. As I stated before, the rules of the time in 1996 made it hard to accumulate top-level talent through free agency. How both players and front offices behaved made it nearly impossible. Strangely, what has brought on player empowerment and the ability to move from team to team is the massive television contracts that have pumped revenue into the league. With the league flush in money, both a salary cap in general and maximum contracts dictated by a percentage of that cap have made it so that Giannis will only receive 25% of his team’s cap if he decides to return to the Bucks in 2021, but he will still make vastly more than Patrick Ewing did when he sucked up three quarters of his team’s cap. Being less greedy individually has allowed for the players to get what they want in other ways, namely the ability to choose where and with whom they want to play. They choose their own destinies now, something that could be considered priceless. Meanwhile, Super-Teams have been great for television ratings, feeding into the cycle and keeping the money machine running.

Back to 1996. If the ’96 off-season were to occur under today’s standards, it would be right up there with 2010, 2014, 2019 and the like in terms of interest. Players that were available and on the market during that off-season include: John Stockton, Alonzo Mourning, Hakeem Olajuwon, Gary Payton, Reggie Miller and Shaquille O’Neal. Naturally, because of the way teams and players handled the cap at the time all but one of those players returned to their respective teams for the 1996-1997 season.

To prove that it was a matter of how teams and players managed themselves, I actually investigated the moves of a number of the biggest free agent spenders that off-season seeing if I could put together something resembling a modern-day Super-Team. I did this based on the free agents involved and the amount of money those teams used to bring in new players. The closest resemblance I could get was with the New York Knicks, having them forgo the signings of shooting guard Allan Houston and point guard Chris Childs. Without those transactions they would be able to sign vaunted rival sharpshooter Reggie Miller in a move that would rival some of the ones that would occur in real life twenty years later. Adding a third piece to create a true big three however would prove difficult. Signing Miller would mean not swapping power forward Anthony Mason to Charlotte for more expensive forward Larry Johnson. Instead, the closest I could get to spending the same amount of money the Knicks did without going over was to instead trade Mason for Portland point guard Rod Strickland. Strickland was traded by Portland in the real-life summer of ’96 for Rasheed Wallace. A Strickland-Mason trade would still supply Portland with a power forward and would give the Knicks a former Assist champion to run their offense. Having not signed Childs, the Knicks would certainly like to have Strickland, but to consider him a member of a true “Big Three” would be stretching it. A squad of Ewing, Miller, Oakley, Strickland, John Starks, Charlie Ward and Buck Williams (who I was still able to add with leftover cash) might be on par with something like some of the 2-star teams we have seen this season (maybe like the Sixers), but to refer to them at the Super-Team level isn’t quite accurate.

Now of course, the Knicks didn’t do what I just described in 1996. The story of what did happen lies in the one exception in the one big free agent that did leave his respective team that summer, Shaquille O’Neal.

In that ’96 off-season Shaq, wanting to be paid like the star player he knew himself to be, decided to spurn the Magic and skip Orlando to head to the Los Angeles Lakers. What he did could be considered the first step toward the player empowerment that we see today.

However, it takes two to tango. O’Neal couldn’t leave Orlando without another destination in line that both had the want and the means to bring him on. Queue Jerry West, former Lakers’ star and top Lakers executive at the time. West oversaw a 1995-1996 Lakers team that saw a 36-year old Magic Johnson come out of retirement (again) mid-season to try to further LA’s playoff chances. Beyond Magic, their best player was one-time All-Star small forward Cedric Ceballos. Predictably, the Lakers lost in the first round of the playoffs to the Houston Rockets and Johnson went back into retirement for good.

The writing was on the wall for West that although a Johnson-less Lakers were competitive, their .571 winning percentage before Magic’s addition would have been good enough for the 6th seed in the West, they were not building a genuinely championship-level team. Stuck outside the lottery, West needed to a way to bring in a star player in some sustainable way, so he forged a relationship with Shaq before and during that summer and did one thing that no General Manager had really ever done before.

He cleared cap space. (That’s right, this big lead up has all been for something a nerd could do with a spreadsheet. Look, it might not be glamorous, but it’s a really big deal).

Much like the moves we see by GMs on the regular today, this strategy had to be pre-meditated. This is proven with my Knicks experiment. The only two teams to bring in more than $10 million worth of new players to their roster and payroll in 1996, a big year of free agent opportunity, were the Knicks and the Lakers. New York did it by apparently having cap room. Ewing’s contract hadn’t exploded yet in 1996 and the Knicks spent $13.8 million on new additions, while only shedding $3.3 mil in non-returning players. Meanwhile, West and the Lakers added $11.9 million total in new players that summer, but their total payroll only increased by $1.1 million. Here’s how:

Basketball-Reference.com doesn’t say for certain, but I am to believe that the amount of money that came off the Lakers’ books with Johnson’s retirement would be about $2.5 million. That would be in line with the salaries he would have made in similar previous seasons. With that assumed, the Lakers then sent center Vlade Divac to the Charlotte Hornets for some kid straight out of high school on a rookie contract named Kobe Bryant. That trade for that netted Kobe was at least in part a move to clear cap to bring in Shaq. A few days later West then dealt rotation players Anthony Peeler and George Lynch along with 2 second round picks for 2 future 2nd rounders. West played quite the price for those future 2nd rounders, but that obviously wasn’t the end game, getting Lynch and Peeler’s combined $3.6 million off the Lakers’ books was.

Between the removal of Divac, Johnson, Lynch and Peeler, West removed $10.8 million from team payroll. How much did he pay Shaq for the 1996-1997? $10.7 million. West nailed it. He did something that was unheard of in 1996, and while no team would even attempt to strategize their cap room in an even greater way until the Magic tried in the 2000 off-season, this would be the beginning of the league never being the same.

Or perhaps it will be the same again someday soon. We live in uncertain times right now and for the first time in even longer than the 24-year period that I have described here, the NBA’s money-making machine is sputtering for circumstances that neither the player’s nor the league can control. It is almost certain that next year’s salary cap will stagnate, probably even go down, and the players and the league are going to need to either get together and decide that either they are okay with that or they need to come to some sort of solution. A financial system built on the basis that revenues perpetually increase is about to break, and while it’s going to be far from the end of the league as we know it, regulations will likely change in some way. If they don’t, then maybe that 25% of the cap that Giannis is supposed get won’t pay him more than Ewing.

Maybe the chemistry of how teams are put together in the league will be altered. But, this is no longer the dark days of the league being riddled with horrible General Managers. Changing times require creativity in order to succeed, the kind of creativity that West exemplified in 1996. Oddly enough, West could still be one of the executives to lead this next generation of changes. We don’t know what the next step will be, but we are certain to find out. In an era where information is more available than ever, someone is certain to get it right. For all the turmoil, maybe the NBA off-season, which has in a way become its second season, will find a new way to excite us.